In recent weeks, Right to Repair has carved a winding path from Washington, D.C., to the literal other side of the earth, to the bins at our collective curb.

Right to Repair: monopoly edition

Last week, for the first time, Apple went on the record about their repair policies in a hearing for the Congressional Antitrust Committee. Their claim? That phone repairs in the hands of an untrained tinkerer could cause injury, and everyone’s safer just leaving it to the pros. (Meaning, of course, Apple itself.) Common logic dictates that higher availability of service manuals would result in fewer repairs gone awry, not less – and yet here we are.

In the next breath, Apple claimed that they lose money every year on repairs. With their retail repair prices this seems particularly difficult to believe, unless they factor warranty and service program repairs in alongside (not to mention free repairs performed under pressure from class action lawsuits). For something that’s supposedly eaten away at their bottom line for a decade, Apple’s fought awfully hard to monopolize repair, inflate its costs, restrict its reach, and incentivize purchases of new products instead – driving up consumer spending and e-waste and… wait… it’s like we’ve heard this song before…

Right to repair: military edition

Right to repair received an unexpected spotlight last week when Captain Elle Ekman from the US Marine Corps wrote in the New York Times about the negative impact of repair restrictions on military operations. Ekman described Marines unable to repair their own equipment in the field, losing months of time shipping engines back to the US for contract repairs, and maintenance bays with idle, broken machinery that no one can touch because of the warranties. Restrictive repair policies such as these deprive Marines of maintenance skills and experience they may need one day on the battlefield, said Ekman, with a broken machine on their hands and no repair contractor in sight.

Right to repair: recycling edition

Recycling has had a long fall from its status as the environmental savior of the ‘90s, curdling into the ineffective specter of our collective environmental failings that we all know it as today. Two years ago, China famously announced their refusal to continue purchasing much of the US’ recycling due to high rates of contamination, and now much technically recyclable, lower-quality plastic is either landfilled or burned right here at home – decreasing availability of recycled plastic products, and increasing pollution from disposal and creation of new plastics.

In multiple grim local-news stories covering this crisis in their own communities, “right-to-repair” gets an optimistic namedrop as a potential waste-diversion tactic. By helping to make repair more affordable and expected, the theory goes, right to repair could result in fewer junked consumer goods, lessening somewhat the flood of stuff in which we’ve abruptly found ourselves drowning.

Right to repair: repairability edition

But not so fast, ray of hope! With Right to Repair bills on the legislative docket of multiple states, industry experts still caution that right to repair does not equal a right to repairability.

Meaning?

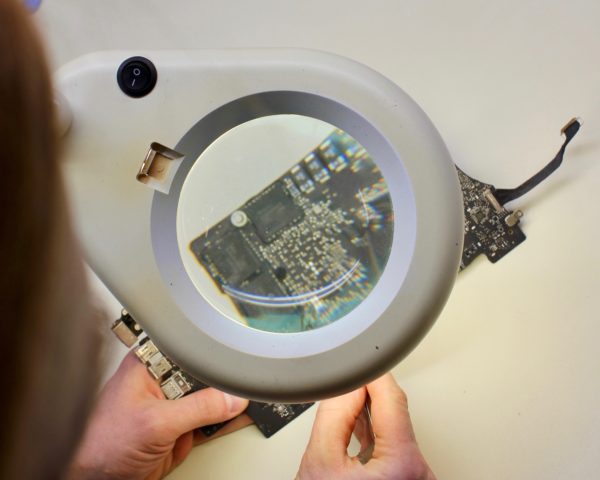

The right to repair is inherently reliant on fixable goods in the first place. If design standards fail to progress, many consumer goods can and will remain, in effect, disposable. A right to repair your electronic device is little more than lip service if you have to destroy it to get inside. (On a related note, the potential for recycling electronic components decreases the more difficult they are to extract from one another in the first place.)

All this means, however, is that right to repair is not the end of the road for establishing a world where repair is expected, accessible, and effective. Rather, it’s starting to look more and more like just the beginning.