Repair Reflections: PRF’s Joel Newman considers how to design things so they want to be repaired

Most of the electronics I have seem to work essentially by magic. Two of my possessions especially: A MacBook Pro and an iPhone 6. When Steve Jobs debuted new Apple stuff, a common catchphrase of his was “It just works.” By this, he meant, magic: How does it work? Who cares! Apple won’t tell, you wouldn’t understand anyway, no one has time to explain. It just works.

Consider, for a second, a typewriter. Typewriters are complex! Pull the cover off one some time and look at all of those interlocking levers, quickly and accurately hammering out letters and advancing the page. How does it work? I couldn’t tell you. But it’s definitely not magic: It gives up its secrets to anyone with a keen eye for detail who cares enough to watch, fiddle with it, and find out.

Typebars on a typewriter strike the ribbon when a key is pressed. Via Wikimedia / Mohylek

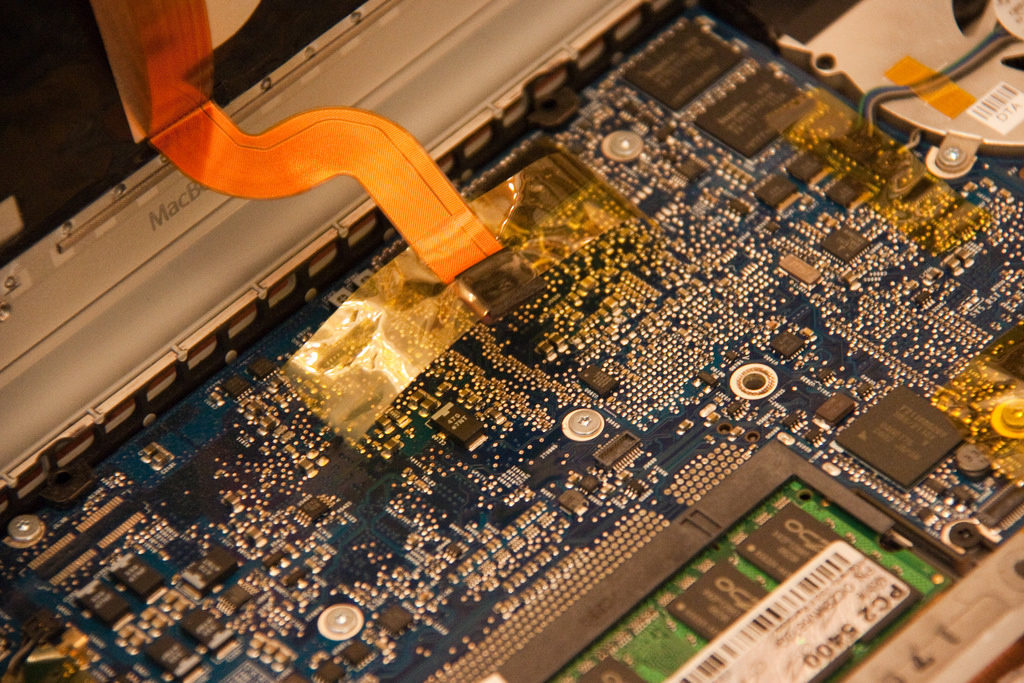

For contrast, pull the cover off your MacBook or iPhone and look at what’s inside. (But first, find yourself a Pentalobe screwdriver, because Apple decided to use proprietary screws to hold their stuff together, in order to keep you out.)

Ok, what is all this?

The motherboard of a MacBook Pro. Via Flickr / Colin Knowles

For contrast, pull the cover off your MacBook or iPhone and look at what’s inside. (But first, find yourself a Pentalobe screwdriver, because Apple decided to use proprietary screws to hold their stuff together, in order to keep you out.) Ok, what is all this?

I’m told there are on and off signals whizzing around on these metal traces, and inside the little blocks and boxes, more signals, just smaller . But, how could I find this out for myself? It’s inscrutable. And how any of this adds up to an email, a website, or Spotify, is, as far as I’m concerned, magic.

I have mixed feelings about Steve Jobs and the cult of Mac, but one especially seductive idea that made Apple what it is today was to make the hardware secondary to the software. Computers and phones are designed to get out of your way: It’s really the app you’re interacting with, and the hardware just provides the medium. And that abstraction opens the door to emphasizing functionality and experience, not specs, operation, and maintenance.

This particular brand of magic seems untouchable, which Apple (and other companies like them) rely on to keep repair of their products a secret and proprietary thing. Their concept of the “Genius bar” suggests that only an elite few are capable of repairing their devices. But on the contrary, genius is not required for some of the most common device repairs. Repair advocates at ifixit.org took this idea to task in the month of February, filming novice “geniuses” with no repair experience as they attempted to fix their own devices for the first time. (The resulting video is a quick and satisfying glimpse behind the curtain of electronics repair.)

The inaccessible air that surrounds the idea of repairing our belongings is not an accident or a natural consequence of consumer goods getting more complex. Repair manuals used to be a standard part of a purchase, but now they are copyrighted and withheld from consumers. We’re talking about computers and phones, but we could make the same points about cars, or running shoes.

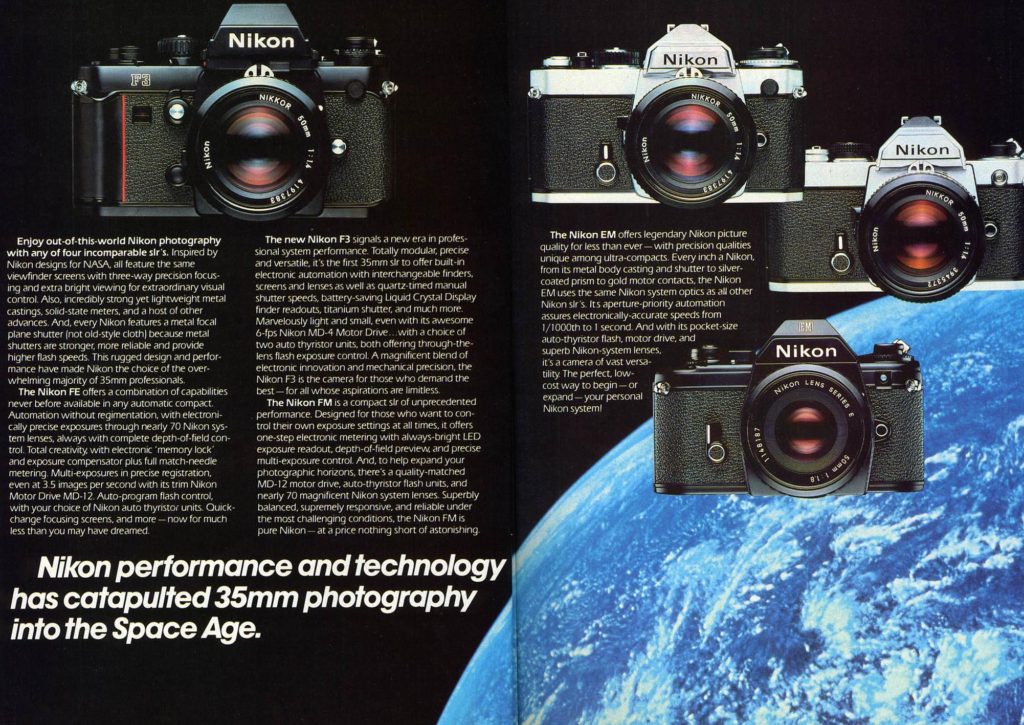

Pick up an old magazine sometime and look at how wordy the ads are, how they talk to you as if you’re weighing the pros and cons of your purchase, perhaps as if you are buying something you plan to have for a long time.

A text-heavy Nikon ad from 1981. Via Flickr / Nesster

It’s easy to imagine how the repairability of the things we buy, our habit of repairing them when they break, and the tools and resources for doing so, have gone by the wayside as the stuff we buy is less an investment than a replacement, and more an experience than a piece of hardware.

At Portland Repair Finder, we talk a lot more about connecting people to repair resources, than we do about designing things for repair. But some things are designed for repair. For example, Agency of Design prototyped a range of toasters designed for repair. One of these, named the Pragmatist is modular, with individual units sized to be easily shipped back to the manufacturer for repair, while the rest of the toaster stays in service.

A modular toast designed for easy, if not DIY, repair. Via Agency for Design

Interestingly, most of these toasters are repairable via that slick, Apple-inspired magic. Could that work? Is the key to repairability just to make the process of repair a seamless, designed experience?

I worked for many years as a bicycle mechanic, and I love that bicycles have no technological magic (well, almost no magic: some bikes do have electronic shifting, sealed suspension damping, and so on). For the most part, they’re all mechanical, and whatever is wrong, you can find out by testing, observing, touching and listening. They invite tinkering, and they teach you how.

The internet of things promises that more and more of our stuff will be, for lack of a better term, smart. But there’s something about tinkering, about understanding how something works and how to fix it when it breaks, that hooks you. Not everything wants to be fixed as much as a bicycle does, however.

If we are to effectively design things for repair, I think the right way to go is to design them for access, and to honestly explain their inner workings, rather than secreting this knowledge away. The challenge is how to dispel the magic of the increasingly small and increasingly complex. How do you design a smartphone that not only can be fixed, but wants to be fixed?

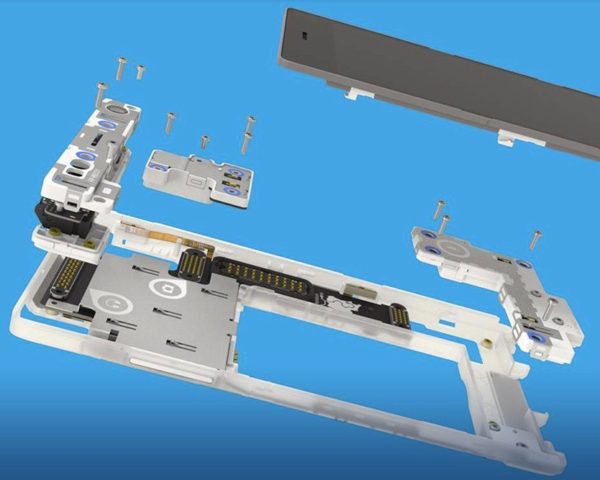

Netherlands-based social enterprise company Fairphone is providing one example of how this can be done. Alongside their goal of ethical and transparent materials sourcing, Fairphone claims to have designed the “world’s first modular phone built for repairability in mind.” They sell all of the phone’s parts separately on their website, so any element that malfunctions can be removed and replaced without having to toss the whole phone. And the idea of repairability is designed into the phone, as not just a vague possibility, but a feature.

The signals that race through a Fairphone’s components are no less magical to me, and no more easily understood. But what I can understand is its hardware, its invitation to tinker. It’s a bridge between the “smart” and the “mechanical,” looping the relationship of hardware and software back around into itself, each supporting and supported by the other – an example of potential for the future of our magical stuff.

PRF’s “Repair Reflections” series offers contemplations, ideas, and story to generate thought and conversation around repair-related concepts in our everyday lives.