Repair Reflections: PRF’s Molly Simas considers the pitfalls of striving for less and the opportunity in reaching for more.

As a child of the 90s in a small liberal town, recycling education featured heavily in my public school experience. I remember a third-grade demonstration where enthusiastic visiting educators – probably college kids from the local university – spread various types of refuse across the grass and asked us to sort them into piles: reusable, recyclable, trash.

Haltingly, we attempted the task. One girl was vigorously praised for placing a waxy Chinese-food container in the “reuse” pile. “How creative!” said the guest teacher. “Chloe is right; you could totally reuse this.”

Like any overachiever would be, I was jealous that I hadn’t thought of this first, but it also seemed silly to me. Whether or not you reused the to-go container, we all knew it was ultimately garbage. Everything the demonstrators had carefully arranged before us, recyclable or not, looked like the trash that collected in the tall grass alongside the roads my school bus traveled each day. My rural home didn’t have disposal service; we burned most of our waste in a barrel in the backyard, a fact I’d learned not to share during these environmentally-conscious teaching moments.

But even my burn-barrel family saved recyclables, carting them monthly to the downtown recycling center, and by the time I hit high school, a lifetime of “green” education and general adolescent self-righteousness combined to in me to produce an insufferably sanctimonious environmentalism. I stopped eating meat. I rode my bike to school. I sprang to extinguish every light in my home the instant it wasn’t being used, much to the frustration of my parents, fumbling for the light switch in pitch-black rooms they’d left well-lit only moments before.

According to my angsty diaries from this time, I felt very enlightened, like I knew the solution. It was clear to me then that each individual was responsible for saving the world through personal choices, and that anyone who succumbed to the mainstream mode of consumption – who, god forbid, used incandescent lightbulbs and took home plastic bags at the grocery store – was selfishly damning us all to a climate apocalypse.

I’m sure everyone can predict the slow slide from grace at the center of this story.

At age 21, I got a car. Around 22 or 23, I stopped militantly bringing my thermos with me everywhere, guiltily enjoying the convenience of to-go coffee cups. My job at a pizza place and the associated free pepperoni slices tanked my vegetarian lifestyle. My 30-year-old self would be severely taken to task by her teenaged counterpart for the simple failure of growing up into a regular member of society – someone who drives to work and shops at (gasp!) Target.

Despite as intolerable as my holier-than-thou attitude might have been, it was born out of a real dismay at the harms of our dominant societal systems – a dismay, it’s worth noting, that I still carry. But righteous behavior is often a privilege of youth, one that age and its accompanying responsibilities has a way of breaking down. It is hard to be pure, especially juggling work and debt and feeding yourself. Not to mention feeding a family, or running a business, or pursuing a degree. It is a lot easier to get with the dominant narrative, and it’s not surprising that, sooner or later, to one degree or another, most of us end up doing just that.

As I’m not alone in my current mainstream-aligned behavior, I wasn’t alone in my most rigidly idealistic phases, either. I had plenty of bike-riding, dumpster-diving, vegetarian company in looking down my nose at everyone else not making the same choices I was. In an essay for Vox, Mary Annaise Heglar points a finger at the dark side of this pretentiousness, which “tells us climate change could have been fixed if we had all just ordered less takeout, used fewer plastic bags, turned off some more lights, planted a few trees, or driven an electric car.”

Heglar says that, more often than not, this environmental one-upsmanship leads ultimately to nihilistic defeat: “The belief that this enormous, existential problem could have been fixed if all of us had just tweaked our consumptive habits is not only preposterous; it’s dangerous. It turns environmentalism into an individual choice defined as sin or virtue, convicting those who don’t or can’t uphold these ethics… If the answers are all in our hands, then the blame can’t be anywhere but at our feet. And where does that all lead? A population beset with shame so heavy they can barely think about climate change – let alone fight it.”

It’s not surprising that this truly global problem is often perceived as rooted in personal failing. All of the messaging we grew up with, after all, indicated that personal choices were the only ones within our power, and that they could truly make a difference. For years, reusable bags and water bottles were the height of “sustainable” swag, passed out widely by environmental nonprofits at Earth Day tabling events.

I do carry a reusable water bottle. I still bring bags to the grocery store. My own lapses in across-the-board environmental adamacy speak not to a broad disbelief in the power of personal action, but rather to a rude re-framing of its role in the bigger picture. I don’t mean to belittle the daily choices; I still think they’re important. It’s just that they’re not the whole story.

As anyone who knew my teen self might expect, I went to college as an Environmental Studies major, where I was slowly and relentlessly crushed beneath the knowledge that corporations, governments, and other entities far beyond the individual scale were decidedly invested in business-as-usual, with no incentive to change. In the face of this understanding, my reusable bags seemed beside the point. In 2010, when the industrial disaster that was the Deepwater Horizon spill leaked thousands of barrels of oil per day into the Gulf of Mexico for months on end, it suddenly didn’t seem like my refusal to drive a car was the magic bullet that would halt the melting glaciers. It all was abruptly, helplessly beyond my reach.

—

“It’s not inspiring to ask people to have a small impact and do less,” said Ellen MacArthur’s voice from my computer speakers. This is where I sat forward and really started paying attention.

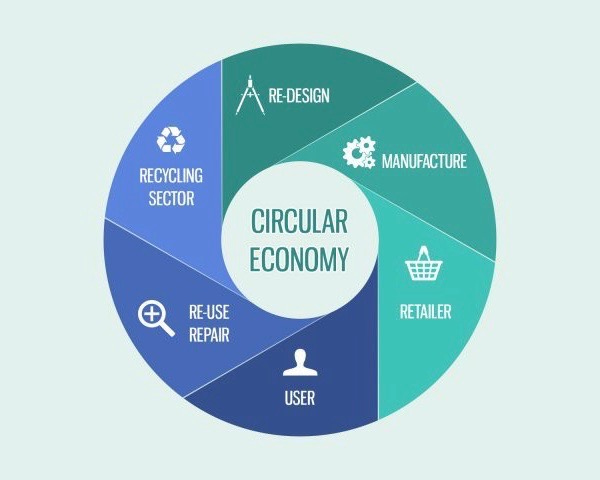

Recently, I was listening to “Explore the Circular Economy,” a podcast in which Joe Iles and Ellen MacArthur were discussing the intricate details of a circular economic model. I’d heard about the circular economy for the first time within the last year, and was intrigued by the concept – an economic system designed to cascade materials through a circular system of function, endlessly looping their energy and use, rather than the linear extract-produce-dispose model we all largely exist within today.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation is singularly focused on accelerating the world’s transition from a linear economic model to a circular one. Their website is a wealth of resources detailing how this can be done, in sectors from textiles to shipping to appliances to agriculture. Earlier this month, they rolled out an immersive learning hub where users can easily access and explore any facet of the circular economy that piques their interest.

The more I learn about repair, the more evident it becomes that repair is being crowded out of the mainstream cultural consciousness in large part due to the dwindling feasibility of repairing our possessions. Often, in our linear economy, goods are made in a way that prohibits repair. Just one example of this would be a toaster made by fusing different structural elements together, rather than a modular construction that would allow removal and replacement of individual parts. One broken component will thus render the entire toaster useless.

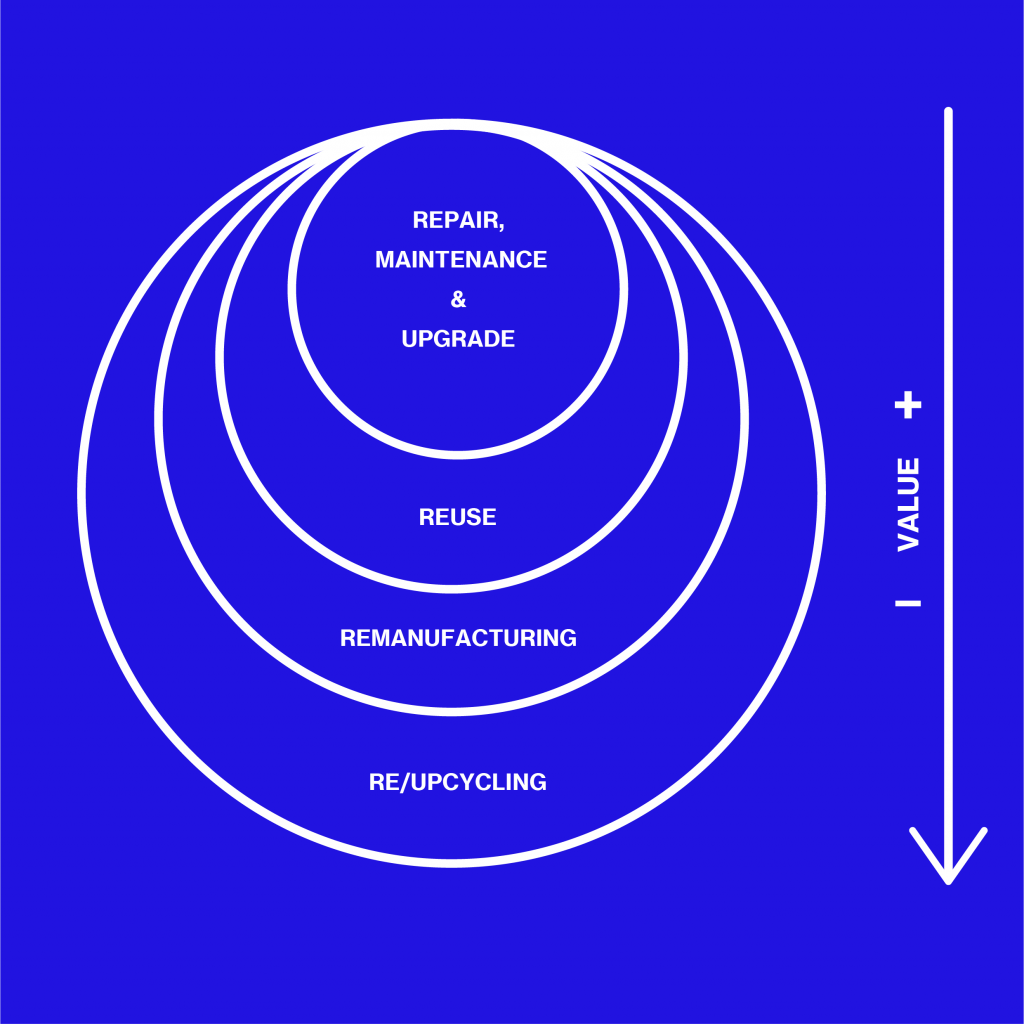

Circular economy is all about retaining value. The better the integrity of the product is preserved, the more value is retained. Image courtesy of sustainabilityguide.eu.

The circular economy is exciting for repair because it divorces prosperity from resource extraction, instead placing value on keeping goods in use at their highest level for as long as possible. For example, in a circular economy, instead of outright owning appliances, one might instead lease the service of functioning appliances from a manufacturer. The responsibility is then passed to the manufacturer to maintain the appliances. They make their money not from producing new consumer goods, but from keeping those already out in the world in good working order. Just like that, the incentive for planned obsolescence is sidestepped, a circular economic model is in place, and repair skills are in high demand.

As our current economic system is predicated on increasing linear consumption, consumer goods are designed more cheaply, to be purchased (and discarded) more often. Repairing throws a wrench in that system, but when goods aren’t designed with repairability in mind, often a repair can be impossible, or more expensive than a brand-new item. With this incentivization to discard the broken and buy new, it’s hard for any individual to prioritize repair, although throwing something basically functional away can awaken uneasy ghosts of conscience – reminiscent of the shame that rises, for some of us, from getting behind the wheel of a car or choosing the disposable coffee mug.

Even though the broken possession is a symptom of a larger system that makes it impossible for us to keep it in use for a longer period of time, we still feel guilty about putting it in the garbage. We still feel like we, somehow, are the ones who have failed.

In her Vox article, Heglar frankly calls placing the burden of the global environmental crisis on the shoulders of the individual likes she sees it: “it’s victim blaming, plain and simple.” How, she asks, can we possibly be held to account for the collective effects of worldwide systems we are helpless to escape? “While we’re busy testing each other’s purity,” Heglar writes, “we let the government and industries – the authors of said devastation – off the hook completely. This overemphasis on individual action shames people for their everyday activities, things they can barely avoid doing because of the fossil fuel-dependent system they were born into. … If we want to function in society, we have no choice but to participate in that system. To blame us for that is to shame us for our very existence.”

What the Ellen MacArthur Foundation understands is that it’s not effective or sustainable to shame people about participating in the dominant systems of our world. Asking people to be smaller doesn’t inspire or empower them. And staying small – simply using less of the options currently offered us – isn’t going to result in the systemic changes necessary to effect real and lasting change.

Instead, the call for a circular economy is an invitation to be big and creative, wild with one’s imagination and idea of what is possible. “We’ve got a massive opportunity to get this right,” says MacArthur on the podcast. “What can ‘right’ look like?”

“Right” can look like regenerative agriculture or plant-based shipping materials. “Right” can look like replacing textile consumption with clothes rental services, or designing for repair and offering maintenance for life. “Right” can look like reframing ownership to look more like access and reframing cities to look more like ecosystems. “Right” can look like your wildest idea that isn’t fully formed yet, waiting to burst forth and transform the way we exist in the world.

I think my younger self always knew, though she fought hard against it, that opting out of society wasn’t the right choice for her. That it wasn’t ultimately sustainable or fulfilling to reject joining the world, no matter how wrong its systems felt. I’m happy to report back to her from the future that a different story about the world is possible – that, in fact, many smart people are working very hard to manifest that system into reality. A system to grow within, not shrink away from. A system to be participated in, not battled at every turn. Maybe even one where garbage isn’t garbage – where even things we’ve learned to see as trash have an opportunity to become something bigger.

PRF’s “Repair Reflections” series offers contemplations, ideas, and story to generate thought and conversation around repair-related concepts in our everyday lives.